Is carbon neutral e-fuel the silver bullet petrolheads are praying for?

Top Gear speaks to ex F1 engineer Paddy Lowe who’s leading the charge

In the early 1900s, an American astronomer named Percival Lowell spent 15 years of his life attempting to convince the world he’d discovered canals on Mars.

A passionate believer in intelligent extraterrestrial life, Lowell penned a series of books explaining why the faint pattern of lines he’d observed on the Martian surface through his Victorian era telescopes proved beyond doubt that the red planet had once been colonised by a tribe of enthusiastic canal builders.

Lowell wasn’t a daft man. A respected mathematician and scientist, his astronomical research would later lead to the discovery of Pluto. But his desperate desire to fit the threadbare evidence to his ‘clever aliens’ hypothesis – to prove true the thing he desperately wished to be true – led him to ditch his critical faculties and become, well, Mr Martian Canals.

Photography: Tom Barnes

When it comes to e-fuel – manmade, carbon neutral liquid fuel that can power any existing petrol or diesel car without modification – I do worry we might have gone a bit Percival Lowell. By ‘we’, I mean people who like internal combustion engines: the noise, the excitement, the convenience, the fact they don’t need to be tediously recharged every hour and a half.

And the promise of a technology that allows us to keep our lovely noisy exciting engines, but without any guilt, any compromise... well, doesn’t it seem almost too perfect? Is there a risk we’re suspending our objective judgement, cherry picking the evidence, because we so desperately want them to be the silver bullet?

In search of answers, I sought out Paddy Lowe, the former F1 engineer now at the vanguard of the e-fuel movement. After three decades building F1 cars that amassed a dozen world championships and more than 150 race wins at Williams, Mercedes and McLaren, in 2020 Lowe founded Zero Petroleum, a synthetic fuel startup based in Bicester, Oxfordshire.

And here’s what you need to know about Paddy Lowe. Paddy Lowe isn’t really bothered about keeping your daggy Honda S2000 going for a few more years.

“Look, I love engines,” he admits. “We all love burning. That’s a very human thing. Combustion engines are exciting. But I’m not doing this from an emotional point of view, to save the motor car or something. We’re not making e-fuels to preserve the engines.”

This, I think, is reassuring. So if not to save our V8s, why is Lowe burning the (carbon neutral) candle at both ends to make e-fuels a reality?

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

“Because you can’t electrify everything,” he explains. “Anything you can electrify, great. I like electric cars. But there are many things in the world you literally can’t electrify. Or that economically don’t work.”

For example? “The simplest one would be an aircraft. You can electrify a little thing that flies one person for 10 miles. But a meaningful airliner literally can’t be electrified. It won’t take off because it would be 50 times heavier [than a jet fuelled craft].”

But battery technology is improving year on year. The energy density of electric car batteries has doubled, give or take, in the last decade. Surely, if that rate of progress continues, it won’t be so very long before a battery powered Boeing is realistic? Afraid not, says Lowe.

“Yes, battery technology is improving, but it’ll never reach that point. It’s fundamental physics. In an electric battery, you’re storing electrons. And those electrons are attached to heavy molecules. That’s dead weight that sits there to carry these electrons around.

“But combustion of a hydrocarbon is a dramatically different density of energy. There may be things we don’t yet know about, but if you talk to a chemist or a physicist, they agree – batteries will never reach the energy density of molecular energy.”

OK, what about hydrogen? “If you built a hydrogen A320, you’d walk through business class, open the curtains to economy, and it would be a hydrogen tank. Hydrogen is not a dense energy store.”

That, says Lowe, is what e-fuels are really about. Not preserving some ancient beloved technology, but because physics and chemistry dictates liquid hydrocarbons are, in terms of weight and space, the only way to feed our most energy hungry vehicles – trucks, ships, agriculture, industrial mining equipment – the energy they need. (Apart from nuclear, but that’s a whole different article.)

So how do you brew up a piping hot batch of e-fuel? First, you assemble your raw ingredients, both free and effectively unlimited: air and water.

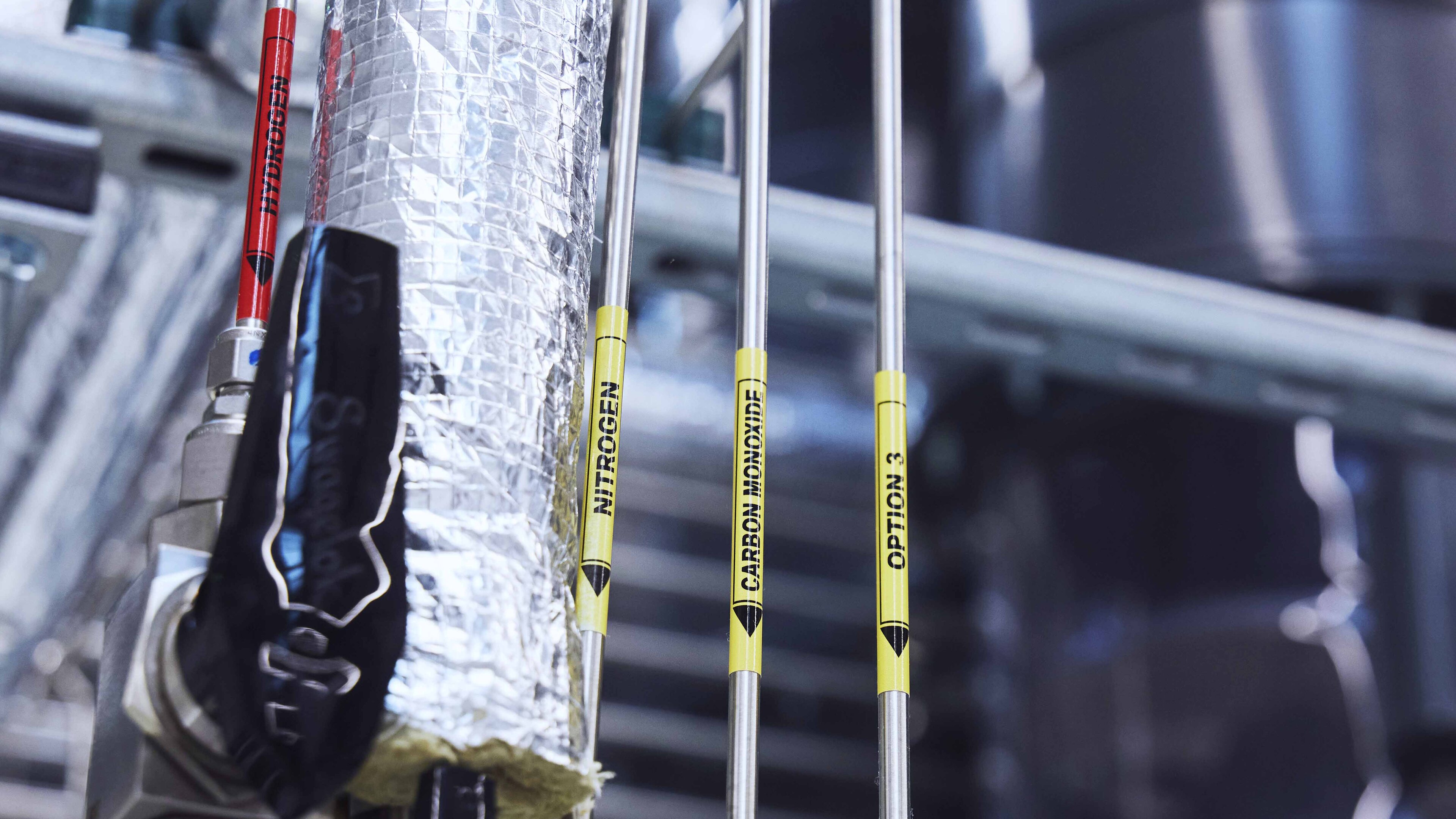

The other thing you’ll need – if you want your synthetic fuel to be carbon neutral at least – is a renewable energy source: wind, hydroelectric, solar. To begin the brewing process, you first use that energy to electrolyse your water, splitting it into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen you keep, the oxygen you ditch.

“So now I’ve got my hydrogen,” explains Lowe. “The other molecule I need is carbon, so you’re going to get CO2 from the air through a process called direct air capture.”

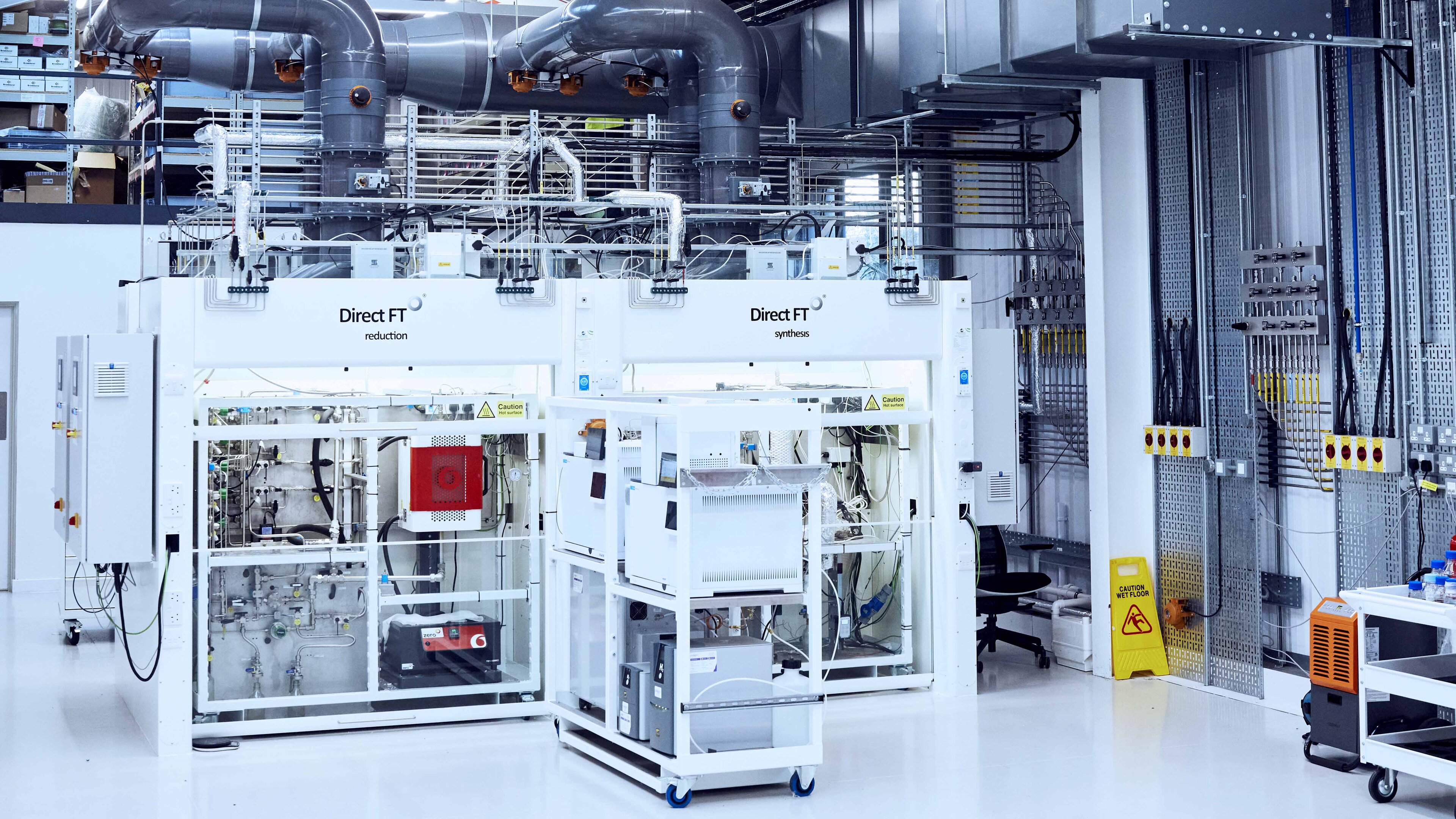

Then you chemically combine your hydrogen and carbon to create liquid hydrocarbons, through a complicated collection of reactions known as the Fischer-Tropsch process. This isn’t a new technology – Fischer-Tropsch was developed a century ago in Germany to turn coal into liquid fuel – but one that’s been fine tuned in recent years by Zero and others at the forefront of e-fuel development. “We have our own proprietary process we call direct FT, which has much higher performance than classic Fischer-Tropsch,” explains Lowe. “We’re able to put those two molecules together to make a refinery grade fuel.”

And when you burn your freshly brewed e-fuel – in your aircraft, supertanker or Vauxhall Corsa – the carbon dioxide that emerges from your tailpipe is the same carbon dioxide you extracted from the air to make the fuel in the first place. True carbon neutrality.

Today, Zero Petroleum brews its synthetic fuel in small quantities at its Zero.1 research plant, using energy harvested from solar panels on the factory roof. Lowe describes current production as “single digit litres per day”, but says 2025 is when the plant will move to generating tens of litres daily – “potentially hundreds, with a following wind".

Which won’t fix global warming overnight. But the point is, synthetic fuel isn’t some flight of sci-fi fancy like the perpetual motion machine or cold nuclear fusion. It’s being brewed right now, powering engines right now (albeit not many, and not for very long). Synthetic fuels work, scientifically. The question is, do they work economically?

Yes, e-fuels are far less energy efficient than batteries. But that’s only an issue when energy’s a limited resource.

E-fuels are massively energy intensive to produce. Stick a kilowatt hour of fuel in your electric car, it’ll propel you around three miles. But use it to generate synthetic fuel for your petrol car, it’ll end up propelling you a whole lot less far. You need energy to split your hydrogen from your water, plus a load more energy to capture your carbon from the air, plus a load more energy to convert your hydrogen and carbon into hydrocarbons.

“About 45 per cent of the energy from the solar panel ends up as chemical energy in our fuel,” admits Lowe. “So you’re losing about 55 per cent. But as we develop and improve the technology, we will be reducing that inefficiency. We think we could get to about 65 per cent.”

Nonetheless, using electricity to produce synthetic fuel is, by definition, more wasteful than piping it directly into a battery. And then there’s the added inefficiency of the combustion engine. Modern petrol cars convert, on average, around 25 per cent of their fuel’s energy into forward motion (and often less). The majority is wasted as heat.

Even if Zero Petroleum one day hits that 65 per cent efficiency goal, that’d still mean barely a sixth of the green energy going into the magic e-fuel machine would actually reach the wheels of your Ford Fiesta. That same kilowatt hour of fuel that sent your EV three miles might get your petrol car around 650 metres.

So if the gas power station on the edge of your local town is pumping out electricity, you’re better using that juice to charge your Tesla directly, rather than run that e-fuel plant you just built in your backyard. But, as electricity grids around the world decarbonise, that increasingly won’t be how, and where, electricity is generated.

“Where are we going to generate the colossal amount of energy we use on the planet today, and currently dig out the ground?” ask Lowe. “You have to generate it in really remote places where nobody lives. Deserts in northern Canada where there’s loads of water for hydro. The outback of Australia for solar...”

Or, closer to home, in the sea. The 3,000 or so offshore turbines in Britain’s coastal waters already generate vast amounts of electricity when the wind blows. The challenge – at least, one of the challenges – is getting that power where it’s needed, when it’s needed.

“A liquid fuel is orders of magnitude cheaper than moving electricity and hydrogen over large distances,” says Lowe. “That’s how we get oil today. It comes from ridiculously remote places called oil wells, and it’s very cheap to move by truck, ship, pipe, whatever. E-fuels are actually an energy logistics product. An energy store.”

Build your e-fuel plant next to your desert solar array, or under your wind farm, and it can also help solve that other issue with renewables: their unpredictable, intermittent generation, and the fact they don’t always make power when people need it. It’s as windy in the middle of the night as is it during the day, but no one’s blow drying their hair then. With a strategically placed e-fuel plant, you can harvest that surplus energy and store it as liquid fuel. Not wasting electricity, but saving it.

Yes, e-fuels are far less energy efficient than batteries. But that’s only an issue when energy’s a limited resource. If the cost of solar and wind power continues to plummet, within a few years the world could – could – have a near limitless abundance of cheap, green energy. At that point, brewing e-fuel isn’t an energy problem. It’s an energy answer.

Should you be so inclined, you can order 20 litres of e-petrol through Zero’s website today. It’ll arrive at the end of 2025 and will cost you £50,000, which still makes it slightly cheaper on a per mile basis than charging your electric car at a UK motorway service station.

Zero’s fuel doesn’t quite cost £2,500 per litre to brew (that £50k batch is a special ‘launch edition’ petrol that arrives in a jerry can personally signed by Paddy). Even so, e-fuels currently remain hugely more expensive to produce than fossil fuels. But Lowe says that number should soon nosedive.

“We model that we can get e-fuels down to the cost of fossil fuels within 10 years,” he predicts confidently. “It might sound extraordinary, but industrial history will show me to be correct. Look at the cost and power of a mobile phone compared to what computers used to cost.

“To make an e-fuel, the feed stocks are free. Sun, air, water. The bit in the middle is a machine, and all machines in history get better, cheaper, more efficient. So, within 20 years, why would you go and try to get the oil from somewhere when you could just make it? Rather than go and find oil in the North Sea, then wait 10 years to get it on the land, just build a synthetic fuel plant...”

But how many synthetic fuel plants – and how much renewable energy capacity – would we require to generate all the e-fuel the world needs? Well, Lowe’s team have calculated that, if you covered 25 per cent of Saudi Arabia in solar panels – it’s fine, it’s mostly desert – you could generate enough synthetic fuel to sate all the world’s current fossil fuel appetite.

And that’s at current solar efficiency. If solar panels become twice as effective at harvesting energy – not an insane expectation, given their trajectory over the past couple of decades – you’d only need half that area of land. And OK, solar panelling 100,000 square miles of the Middle East might seem mad, but not that mad, right?

E-fuels might be the golden ticket. They might not. But if they do fizzle out, it’ll be down to macroeconomics, geopolitics and infrastructure, not science

And, of course, the point is that e-fuels won’t need to replace the world’s entire fossil fuel consumption. They’ll be part of a mix.

“For the green energy transition to happen, you need three tiers,” says Lowe. “You need renewable electrons. You need green hydrogen, for example for making steel. You can’t make steel with electrons. And then you need e-fuels.”

Synthetic fuels, on their own, won’t be the magic one stop solution to our planet’s green energy needs. They’re not the silver bullet. But they might well be part of the silver arsenal.

Paddy Lowe isn’t developing e-fuels to preserve the combustion engined car, or noisy motorsport. But he admits it could be a happy byproduct. When I ask him which car engine he’d be most pleased for his e-fuel to save, he nominates the V10-era F1 units.

“One of my biggest regrets in F1 was that we lost the V8, the V10, the V12 engines,” he admits. “We had engines on the dyno that were going to 21,000rpm. The noise and the performance, it was just mindblowing. It was disappointing when they got cut back. But synthetic fuels provide a pathway to bring that back. You can have your cake, and eat it, and feel good about yourself.”

As business pitches go, it’s not a bad one, right? Come for the guilt free air travel, stay for the guilt free noisy motorsport...

The world being as it is nowadays, it’s not often you emerge from a conversation about the future feeling anything other than deep despair. But after an hour chatting to Paddy Lowe, I’m left with the strangest of sensations. I believe they call it... optimism?

At the very least, I emerge feeling reasonably confident I haven’t gone full Percival Lowell. E-fuels might be the golden ticket. They might not. But if they do fizzle out, it’ll be down to macroeconomics, geopolitics and infrastructure, not because of science.

And if synthetic fuels do end up saving our engines, that’d merely be a fortunate side effect of saving civilisation from a global warming heat death. Which feels a valid reason to root for their success, right?

“We should all be optimistic about what can be done, and what we need to do,” says Lowe. “We’ve just got to get on with it and stop faffing around.”

Trending this week

- Top Gear's Top 9

Here are nine crossovers we'd actually want to own