Is the flying car close to reality?

It's all very well having a Ferrari, McLaren or Lambo. But they're still earthbound and therefore inferior...

Juraj Vaculík is not an engineer or aviator. In fact, he’s the first to admit that he’s an unlikely avatar for the flying car, a concept that has fired a thousand sci-fi movies without ever actually getting off the ground. But nor is the man behind AeroMobil’s magnificent flying machine an entrepreneur dilettante.

“Freedom to travel”, he tells me, “is what propels this idea. It’s deeply rooted in us, as people. I grew up in a former Communist country, and we used to stare across the River Danube at Austria and imagine what life must be like. I have personal experience of how a small group of people can change everything. Now I am ready for another revolution.”

Words: Jason Barlow

Photography: Mark Fagelson

Vaculík was studying theatre direction in Czechoslovakia in 1989 when the spirit of revolution that razed the Berlin Wall spread east and ultimately ripped through the Iron Curtain. The young Vaculík was one of the prime movers in the so-called Velvet Revolution, which soon saw rebel playwright and human rights activist Václav Havel elected President. Now, in an admittedly unexpected twist of fate, he wants to democratise the skies. “Our transport infrastructure is at breaking point. We need to find the intersection between road and air,” he says, gesturing to an empty blue sky. “Remember when the cellphone first appeared? Some observers said its growth would be linear, not exponential, and we all know what happened next. We believe the flying car has that potential.”

Slovakia is not Silicon Valley, but don’t be too hasty about making judgements. AeroMobil’s HQ is an impressively polished facility on the outskirts of Bratislava, a region that currently produces more cars per capita than anywhere else in the world, home to huge PSA and VW manufacturing facilities, and soon a shiny new £1bn JLR factory. Costs are lower in eastern Europe while still guaranteeing access to the EU, but there’s also massive expertise here. By the time an old school friend called Stefan Klein started selling him on his vision for a flying car, Juraj had prospered in the advertising industry and was supporting start-ups in Slovakia.

AeroMobil was founded in 2010, and the first prototype, v2.5, appeared in 2013. It looks a bit shonky now, but at a global aviation gathering in Montreal, the industry acknowledged that there was more than just pie in the sky going on here. And it flew; not far, but far enough. Ten months later, v3.0 appeared, the work of 12 people, deepening the proof of concept, and developing the company’s IP to an extent that AeroMobil now found itself registering multiple patents and on the radar of heavyweights like NASA and Boeing. “We presented v3.0 in Vienna,” Juraj says, “which was personally very emotional for me. We got a great response, but of course plenty of people still looked at what we were doing as a… curiosity. How credible can a bunch of Slovaks in a big garage building a flying car really be?”

He approached more investors and industry OEMs than he’s ready to admit, and faced down a lot of rejection. It was deemed just too risky. But when a consultant called Glenn Mercer, McKinsey & Company’s former head of automotive practice, told him he was really on to something, and introduced him to a guy called Antony Sheriff, the path to v4.0 was set.

Sheriff is now chairman of Princess Yachts, but you might remember him as a former VP of Fiat and MD of McLaren Automotive. Having presided over the development of the SLR and the creation of McLaren as a standalone carmaker, Sheriff is a man with a finely honed bullshit detector. “He told me he flew to Vienna not knowing what to expect. When he arrived, he spent 20 minutes examining every element of the car,” Juraj recalls. “Finally he said, ‘OK, I’m in.’ His involvement has made a huge difference, as we move the project towards the production phase.”

McLaren’s ex-boss tipped off a former colleague, Doug MacAndrew. Doug began his career working on the original Discovery, and developed the new Mini, before moving to Woking. “Antony said, ‘You really need to check these guys out,’” he tells me. “I looked at v3.0, and was searching for the smoking gun. I figured there had to be a reason why no one had ever done a flying car, why it just couldn’t happen. But I couldn’t find it.”

A decade or two ago, he probably would have. But he agrees that a number of factors are converging to turn the mirage that is the flying car into a reality. Primarily, the tech now exists to merge what are two wholly different if not incompatible sets of requirements, in engineering the thing so that it actually works, but also in navigating the labyrinthine legislative framework – both in automotive and aerospace. Design software and CFD (computational fluid dynamics) mean that the tools now exist to prove the physics virtually in a way that a start-up could never have imagined previously. Finally, modern avionics are now vastly lighter and easier to package. “V3.0 has racked up 50 flying hours, and we’ve done many thousands of flying hours on the simulator, so we know what v4.0 can do,” Doug says. “The next phase is to build a validation prototype.”

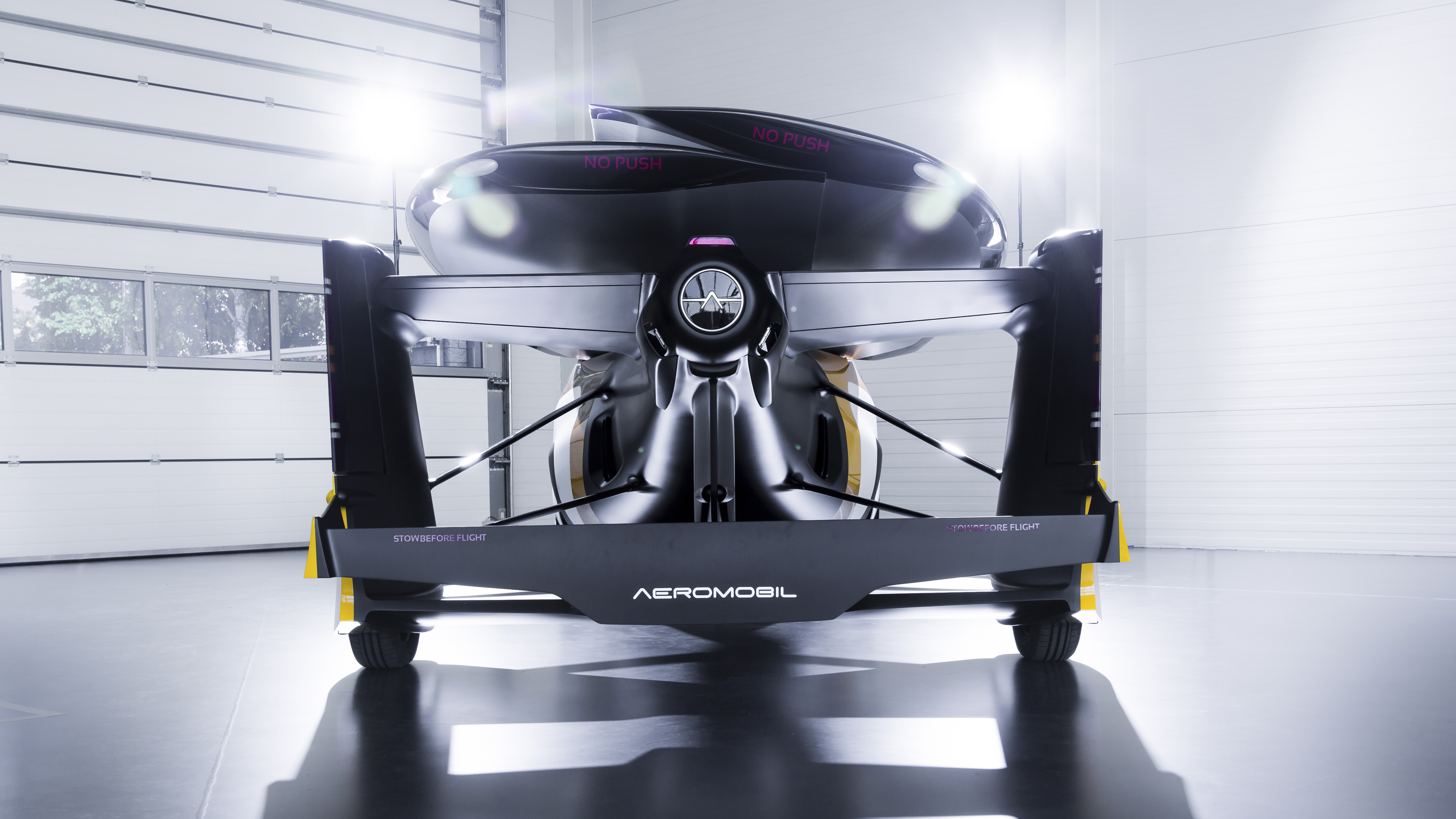

Like all aircraft, the AeroMobil is ruthlessly weight-optimised: its maximum take-off weight is 960kg (720kg without occupants or fuel); get up close to it, and it’s clear that it isn’t just plausible, it’s convincingly engineered and expertly executed. “We’ve maxed out on the use of carbon-fibre composites to achieve the weight targets we’d set ourselves,” MacAndrew says. True, its form and surfacing posits a third way somewhere between car and plane without looking like either, but if you picture a McLaren flying car you wouldn’t be far off.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

Serious credit must go to designer Adam Danko. Car designers, in their more fanciful moments, tend to describe the body-side as a fuselage; the AeroMobil genuinely has one, and it’s beautifully sculpted. In fact, it gets less car-like the further your eye travels along it and more intriguing. The waisted fuselage and empennage – the rear section that houses an aircraft’s stabilising surfaces – culminates in the mounting for the propeller, but does such a convincing job of looking like a jet turbine that more than one person has asked the team if they’ve thought about doing exactly that.

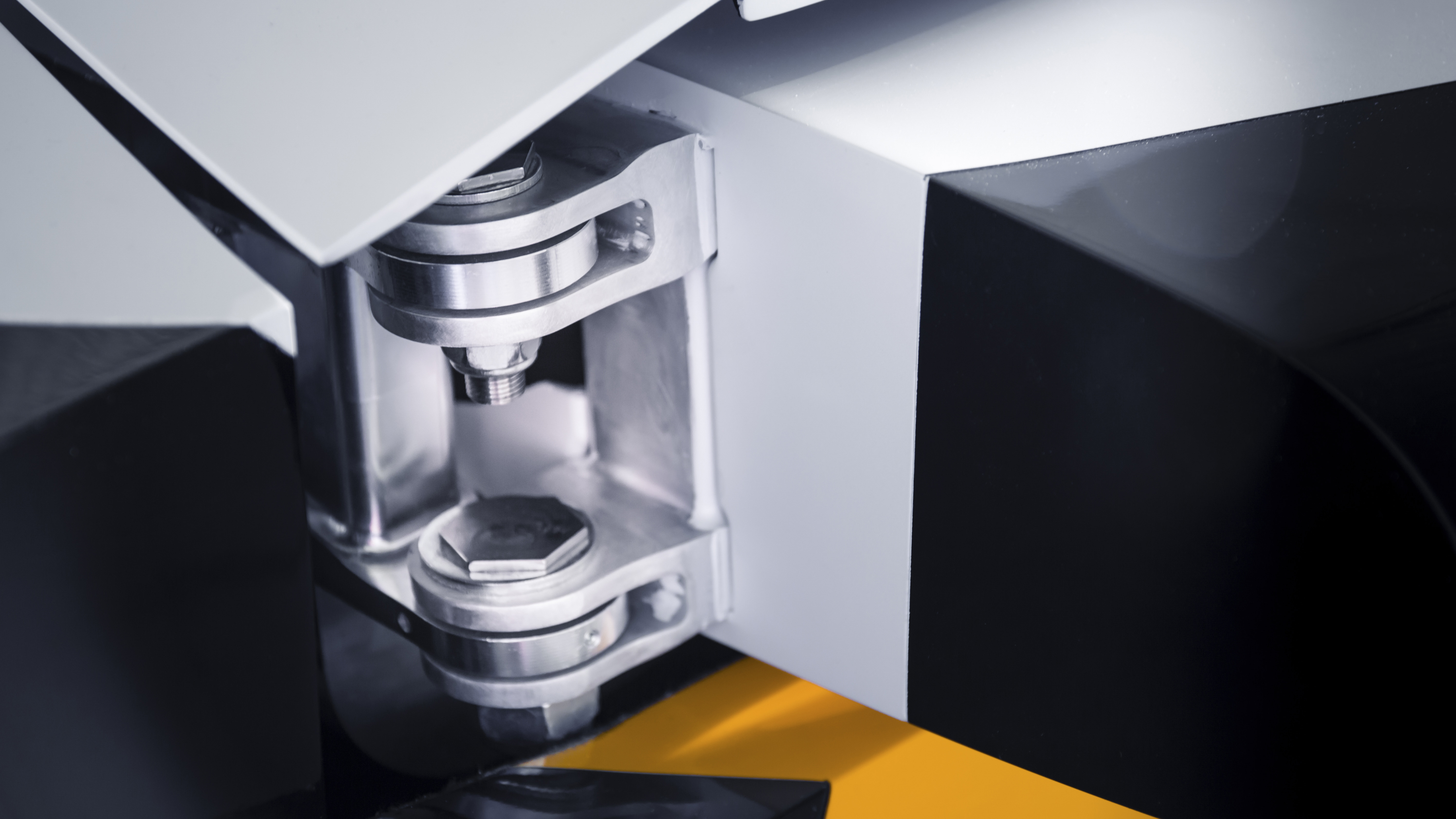

The chassis is similar in concept to McLaren’s Monocage: it’s a pre-preg carbon tub with an extruded aluminium crash box mounted on the front. The ducts on the side funnel cooling air into the engine, and a second set ahead of the rear suspension struts dispel exhaust gases. The central section consists of an integrated carbon cradle that houses the power unit, with a ‘cruciform’ underneath for additional rigidity, and mounting points for the wings. These motor on actuators into a stowage position above the fuselage on beautifully designed pivots, whose ‘load case’ benefits from aerospace rigour to withstand six times the safety requirement. The wings themselves are also made of carbon composites, and feature flaps for additional surface area, something of a novelty in an aircraft that fits the ‘general aviation’ remit (a light plane rated to fly at altitudes up to 10,000ft). It takes three minutes to switch from car to flight mode.

From behind, you really could be looking at an enlarged LMP1 endurance racer, fitted with the world’s biggest diffuser. Yet there are strips of light down the tail-fins, and because it’s a car it also needs a bumper. This deploys on the road, and folds away in the air. The propeller blades also stash away in an ingenious housing. The whole thing is a serious challenge to everything you thought you knew about cars and planes, but in a good way. It’s also a whopping 5.9m long, the optimum length for providing good pitch control, longitudinal stability, and to deliver a flying experience accessible to owners who lack the skill set of a Hollywood stunt pilot. You will need a PPL, though. And balls of steel when reverse parallel parking.

The AeroMobil is powered by a Euro 6-compliant 2.0-litre turbocharged four-pot that acts as a generator for twin electric motors producing 110bhp, driving the front wheels, which themselves slide out of the body on actuators to provide the necessary track width for stable road use (much engineering effort has gone into developing the suspension geometry). The ICE power unit delivers 300bhp in flight mode, with direct drive to a variable pitch propeller, and the cruising range is 750km (466 miles) at 75 per cent throttle. Prodrive has developed the engine specifically for AeroMobil, another gold standard indication of ‘proof of concept’. MacAndrew says the engine is capable of much more, although they’re being deliberately conservative, and on skinny rubber it’s not about pushing any handling envelopes. “OK, so it can only do 100mph, but can you think of a better car in which to make an entrance?” Doug notes drily.

A Smart roadster lurks at the back of the hangar: its interior packaging has provided the model for the AeroMobil’s cabin. You drop into it almost like you would a single-seater racing car, and the seats are similar in concept to a LaFerrari’s: the cushion is fixed to the tub, with an element that slides out under your thighs, and a movable pedal box. It’s elegantly done, and the Garmin display systems are state-of-the-art. The glass area in the doors extends above your head for the necessary in-flight visibility, and safety features run to a ballistic parachute system.

It’s a colossal feat of engineering and imagination. It also pioneers some clever tech that may well find its way into the flying Ubers and Amazon drones that are on the horizon. Note, also, that Larry Page, one of Google’s founders, has invested $120m of his own money into flying cars. AeroMobil’s IP is clearly highly prized, and the Slovakian government is on board, too. It costs from $1.2m, so you’ll need to be a well-heeled early adopter: Gisele Bündchen, Harrison Ford, and Jay Z are all on AeroMobil’s target list.

“Why now?” Juraj answers. “Because we desperately need this sort of innovation. We need to make medium-distance travel faster. The World Bank is predicting that $8tn is going to be spent on infrastructure in China and Africa in the next decade. That means more deforestation and damage. Look up! AeroMobil is a niche product, but it will prove the market, prove the technology, and prove the brand.”

For once, the sky truly is the limit.