How does a rotary engine work?

Always wanted to know what everyone was talking about with spinning Doritos? Let’s dive in

What is a rotary engine?

In simple (verging on simplistic) terms, it’s an engine with one or more rotors that rotate – go figure – instead of pistons that reciprocate. The basic principles of internal combustion – suck, squeeze, bang, blow – still apply, but the method by which this is put into practice is where the difference lies. More on that in a bit.

It’s also used to refer to those big engines from old aeroplanes, where a whole heap of pistons are arranged in a circular shape around an eccentric central crankshaft and actually rotate around it. It’s a sight to behold, no doubt, but not what we’re talking about here.

While you likely associate the rotary engine with Mazda, given they’re the only car company to have had any kind of notable consumer success with it, the rotary has been used in cars from Citroens to NSUs, as well as motorbikes, helicopters, light fixed-wing aircraft, drones, jetskis – you name it. We’re sure if you looked hard enough, you could find someone who’s attached it to a lawn mower (now there’s an idea) or a fishing boat, but that’s a pretty wide distribution nonetheless.

The rotary is actually pretty special, given it’s one of just three engine types humanity has ever invented. The first is the one you’re most familiar with – pistons – which can then be sorted into four-stroke and two-stroke, diesel, petrol and so on. The second is turbines, which you’ll be most familiar with from your last Ryanair/Jetstar/Delta flight. And the third is rotaries. That’s about it, unless you start count rockets.

How does a rotary engine work?

Oh, can we just say ‘pixie dust and the tears of racing drivers’ and move on?

No? Fine. This is going to get a bit conceptual, so buckle up.

Imagine an oval that’s been ever so slightly pinched in the middle, for a barely perceptible figure-eight shape. Now imagine a triangle with bulging sides inside that slight figure eight, doing a kind of waltz movement around and around so that the long, curved side of the bulging triangle creates four distinct ‘zones’ in the figure-eight as it dances.

These four zones are the four parts of the combustion cycle – intake, compression, ignition, exhaust. The genius of the rotary is that one rotation means three separate power strokes, as opposed to four-stroke piston-engines, which – as the name suggests – only make power on one movement out of four.

As one side of the triangle is moving away from the intake, it’s drawing in air-fuel mixture. And as it moves away, the next side along is compressing the mixture. Which is then ignited, a) allowing the expanding gas to push the rotor, and b) making power. But as that side of the rotor is being pushed by combustion, it’s pushing the next side of the triangle along to vent the exhaust gases. Amazing stuff, really.

On the inside of the triangle is a gear, which kind of hula-hoops around a smaller gear attached to something called an eccentric shaft. Yes, many dances make up the rotary engine. Anywho, this eccentric or ‘E’ shaft looks a bit like a big camshaft with gigantic lobes. And it functions in a similar way, but to a different end. While lobes on camshafts convert rotating movement to reciprocal – to push valves up and down as the perfectly round bit of the shaft rotates normally – the ‘lobes’ on an eccentric shaft allow the rotor to pirouette inside the housing while converting the energy from the Dorito dance into regular rotations.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

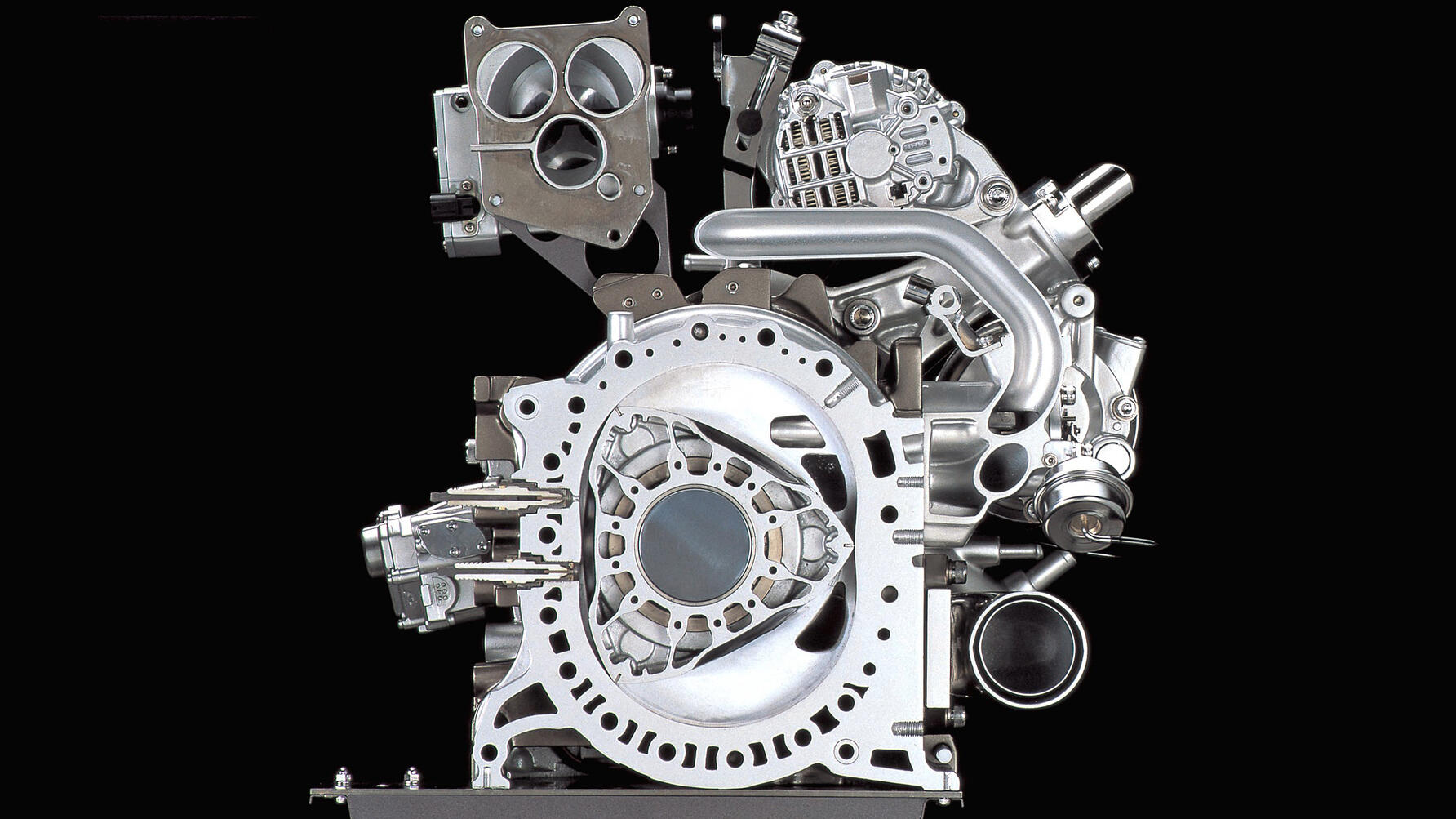

Pictured: Mazda's 'Renesis' rotary engine

How is a rotary engine different?

In a lot of ways, it’s the same idea as any other petrol engine. Rotaries still take fuel, mix it with air, compress the mixture, ignite it with spark plugs, use the expanding gas to perform mechanical work and turn a shaft, then eject the spent gas from the combustion chamber.

Where the rotary engine differs is... roughly everywhere else. As we’ve already talked about waltzing Doritos that hula-hoop around an eccentric shaft, it’s safe to say that there’s quite a bit to wrap your head around.

The number of parts needed to build a rotary engine is a fraction of a reciprocating engine, and many of the inherent problems of piston engines – and the intricate engineering needed to overcome them – are obviated purely by the rotary’s design. More on that... well, now, actually.

What are the good things about a rotary?

Well, there’s BRAP any number of BRAAAP positives about the BRAP-BAP-BAP-BAP rotary engine, such as the small size, light weight, low parts count, ease of manufacturing, BRAAAAAP... And, of course, the unique, raucous and ultimately unmatchable sound, in case we didn’t already telegraph that earlier. The sound is part motorcycle, part F1 car, and all good. Not even turbos – infamous sound deadeners that they are – can foil the fury of a rotary in full flight.

And it will be in full flight, too – rotaries are legendary for the way they rev up, and indeed how high they can rev. That’s because the rotor... well, rotates, rather than reciprocates. So each part of the combustion cycle keeps propelling the rotor in the same direction, rather than overcoming the inertia of a piston to stop it and send it back the way it came. While driving, that means razor-sharp responses to throttle inputs; while building, servicing and rebuilding, that means a kind of simplicity that even old-school Detroit V8s couldn’t hope to match.

The rotary engine has no need for the likes of crankshafts, connecting rods or complex valvetrains. In fact, there’s no need for valves – the rotor takes care of the whole deal with a few ports.

So when it comes time to tune a rotary engine, that means getting out the Dremel and making merry with the intake and exhaust ports. While that’s obviously an avenue for tuning with a reciprocating piston engine, you’re doing more than you’d think by altering the ports on a rotary – you’re actually changing the timing, too.

So, if you are after the aforementioned BRAP-BAP-BAP et cetera, it only arrives after you’ve fiddled and fettled the intake and exhaust ports for more airflow and greater overlap. So now you know – there’s science behind brap.

What are the bad things about a rotary?

Would we be coming down too hard on the rotary if we said Concorde-rivalling fuel use, longevity you can measure with a stopwatch, and barely enough torque to strip a Phillips-head screw? Well, yeah. Not to sound like Spinning Dorito apologists or anything, but it’s not all that bad.

The oft-repeated saying of ‘nothing in life is free’ applies here – rotaries have a series of advantages over reciprocating engines, but that means accepting certain attendant drawbacks. In a nutshell, that’s usually fuel (and oil) use, shorter intervals between needing serious mechanical intervention and just the feeling of knowing you’re driving the Chekov’s gun of engine configurations. It’s going to go bang; just where in the fifth act that happens is the suspenseful part.

In the interests of balance, we should point out that anyone mechanically inclined enough to run a) a classic car or b) a dirt bike will be able to run a rotary-engined car without any issues. Of course, an entire twin-rotor engine (or triple, if you’re a lucky beggar with an early Nineties Cosmo) is going to be more involved than a standard carb-fed classic or single-cylinder thumper, but the mindset that rebuilds are just part of the ownership experience is already there for Triumph TR3 owners and trail riders.

But, if you’re interested in a bit more of a gap between replacing apex seals (the most common big job on any rotary engine – which involves the equivalent of open-heart surgery each time – the (entirely unofficial) expert advice is often to premix a bit of two-stroke oil in the fuel tank. Yes, really.

It’s to prolong the life of the apex seals with extra lubrication, apparently, even though rotaries already have oil injection. Apparently not enough, or in an even enough dispersal across the apex seal. Also, let’s address the obvious concerns you might have about running your RX-8 on two-stroke: at the ratios the expert we asked said, the ratio was around 1:400. That’s a fraction of your average two-stroke, and won’t block injectors or foul spark plugs. Greta might want a few words with you, mind.

When is Mazda going to make that RX-Vision into an RX-9, so I can live out my quad-rotor dreams on the road?

While there is little we’d love more than for Mazda to give the rotary engine a quad-rotor, 10,000rpm swan song – particularly if it arrived in a shape as gorgeous as the RX-Vision – there’s every chance we’ll have to console ourselves with a virtual version in Gran Turismo Sport.

But that’s not to say that the engine masters at Mazda don’t love the idea as well; while Mazda was developing the rotary for the MX-30 R-EV – capitalising on its small size and low weight by using it as a range extender – the obvious question was... well, obviously bandied about a bit.

After all, as a muckety-muck at Mazda said: “The dream of the engineers is that someday we will have a sports car with the rotary engine."

Trending this week

- 2026 TopGear.com Awards

"Engineering at the cutting edge": why the Ferrari F80 is our hypercar of the year