Restogods: Porsche 911 by Singer vs Alfaholics GTA-R

Which driver-focused restomod delivers the biggest hit?

Immediate satisfaction? You’ve come to the wrong place. Because you shouldn’t expect to get into Singer’s Porsche or the Alfaholics GTA-R and adore them right away, first time out, instantly. You’ll think you will, because you’ve been gawping at them across the car park. Both are flypaper for your eyeballs. The diminutive Alfa with its oversized headlights giving you a look of wide-open innocence, a glimpse into its virtuous soul; the Singer’s perfectly polished iconography, a fluent rhythm of shape and stance. Visually magnetised, you stand there and you know – you just know – precisely what each is going to be like to drive. How the controls will respond, the sounds they’ll make, the sensations they’ll deliver.

And if you’re on the right road on the right day, maybe you’re correct. But the right road is not the wriggle out of an industrial estate south of Bristol and up the M5 that was my introduction to the Alfaholics. The noise was a triumph from the word go, but nudging past a litter of vans and trucks what struck me most was that I could barely turn the steering. Wrists and forearms weren’t enough – it was only when triceps got involved that the high-set, prominent wheel would do as bid.

And then the motorway. Busy and raucous inside, mechanical gnash and thrash from up front, the din of thunderous truck wheels, being eye-to-eye with their wheelnuts, aware of how small and ill-protected you are – and where’s the get-me-out-of-here torque? Ah, there isn’t much. Truth be told, if you, like me, are mainly used to driving modern stuff, getting into the Alfaholics is a bombardment. It’s far closer to doing distance in a Caterham than I’d expected, so I emerged at our south Wales rendez-vous slightly shell-shocked. I didn’t feel that I’d kept pace with the GTA-R. I was driving it, but not communicating with it. It was the handshake (remember those?) where all you get is the other person’s fingers – not satisfying for either party.

But I got out, looked back and immediately forgave it for every one of the last 65 miles. Too pretty for words. But now I was also seeing beyond that, noticing the lack of bumpers, how squat it is, the rear wheels tucked so far up inside the arches, the boot’s race latches, and – best of all – the drilled door catches. Weight saved, track ready. It’s only the supercars of today that claim the duality of being able to cruise comfortably as well as deliver a hit like a thunderclap. Well, they claim duality, the reality is compromise.

There is no compromise in either the Alfaholics or the Singer. Both are products of singular vision and determination. No committees involved or politics to negotiate (mostly, the legal situation between car firm and restorer is a matter for the companies alone), just the intention to be the best they can be. Of the five cars we had along (the others on this day of days, as you’ve hopefully already read in Chris Harris’ piece were an Eagle E-Type, Aston DB5 Continuation and GTO Engineering Ferrari 250SWB), these two were the ones that felt most detached from their origins. Also the ones that focused most on being great to drive. The others are about the experience of driving, but with the 911 and Alfa it goes deeper than that – the reward of driving. Both entice, demand that you get involved, aren’t just carried along on a wave of immaculate nostalgia. It’s why we’ve put them together here.

After the Alfa the Singer is bigger, rounder, the lines less cleaved, the shaping more Titian (please don’t read that as mortician…). The symmetry soon strikes you. View it from dead behind and your eyes are magnetically pulled to the centre exit exhausts, then your view broadens, out past lights and over haunches to the rear wheels, poking out just so from under the arches. Round the front, the central fuel cap and gorgeous headlights lend the nose a similarly clean aesthetic. Then you notice the materials, especially the nickel detailing. It’s exquisite, the whole car reeks of dark obsession and endless OCD.

Very soon you realise that almost nothing you’ve ever driven moves along tarmac better than this

And then you get in, the pedals are way over to the left and you wonder what on earth went wrong. And you remember. Ah, old Porsche 911. And you begin to drive. Ah, old Porsche 911. The nose porpoises a little, the steering lightens as the rear engine levers a little against the back axle. Thinking of the Singer as a new car? It’s not.

It’s cleverer than that. Over the last 60 years Porsche has taken a sports car concept that’s great for packaging, a nightmare for dynamics and honed it to a point others can only dream of. The latest 911 is more practical than any other sports car and handles more faithfully too. Singer isn’t interested in that. It wants to deliver a Porsche experience that celebrates the idiosyncracies that gave the car such charisma, yet dials out the inherent evil. So Singer takes as its starting point a 964-generation car (built from 1989 to 1994) and fettles that. I say fettles, but the attention to detail you see outside is as nothing compared to what’s gone in underneath. Some highlights: the donor car is stripped back to a bare chassis and extra strengthening is added, almost all body panels are carbon apart from the steel doors, the steering is borrowed from the 993-gen car, while the big brake option is derived from the 993 twin-turbo.

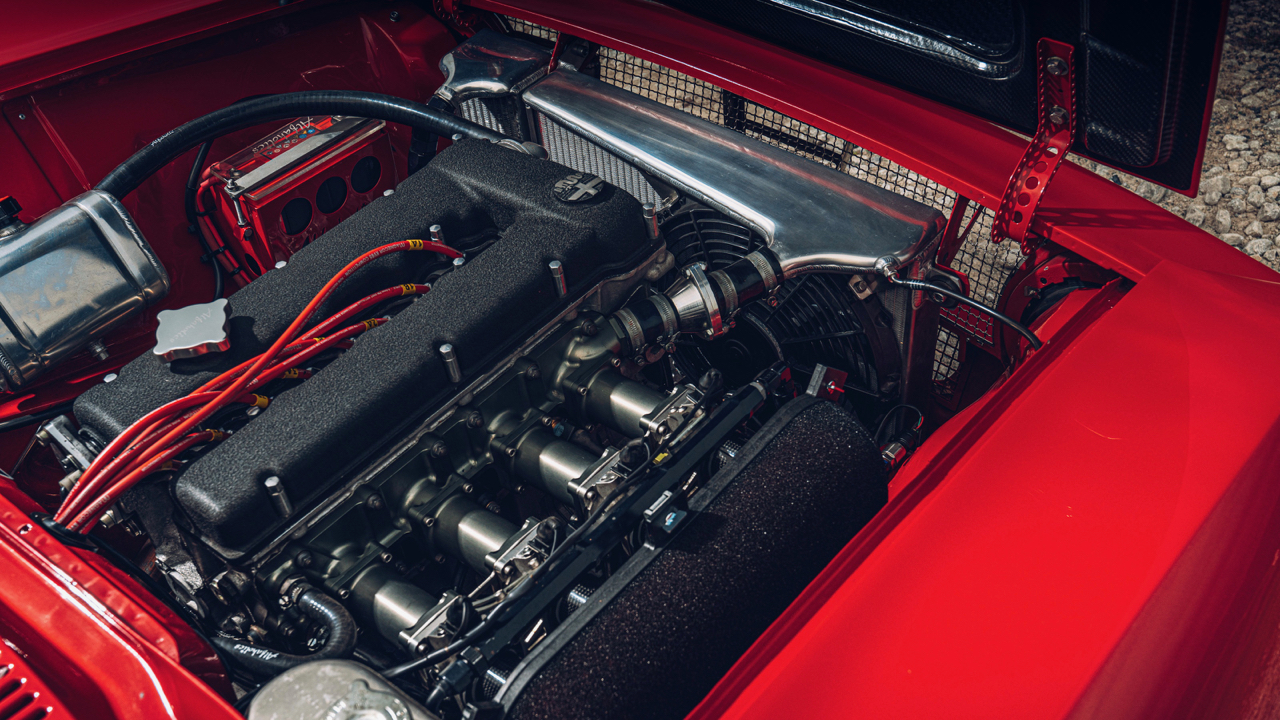

And then we come to the engine. This one’s a 4.0-litre developing almost 100bhp per litre. It retains the basis of the original flat six motor but the crankshaft, oil pump, pistons, cylinders, connecting rods, cams, cylinder heads, throttle bodies and intake system are all new. Singer claims 0-60mph in 3.3secs and 0-100mph in 8.2secs. That’s as quick as a 992-gen 911. It’s also the least interesting and relevant thing about the whole car. Yes, it’s fast, modern fast. But that is such a small facet of its performance that you never think about it, and have even less desire to test it. Yet that one irrelevant facet also happens to be the only thing of any interest about almost every electric performance car, while here there’s such richness of experience that the acceleration it’s capable of is nothing more than a footnote.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

It’s such a wonderful engine to use – smoother and less guttural than I expected, but with all of the flat-six highlights we know and love, the rich torque build, the response, the mechanical thrash of valves and pistons from behind you. The one disappointment is the engine redlines at 7,200rpm. At that stage it doesn’t quite feel like you’ve reached the crescendo – not least because the rev counter immediately in front of you and painted bright orange reads to 11,000rpm. The forthcoming DLS version will undoubtedly rectify that.

It’s the one anti-climactic thing about the car, and even then I sense it’s only a slight let down because the car it faces here has one of the most furious engines I’ve ever encountered. Four cylinders dull? Let the GTA-R put you straight. 2.3 litres of manic, frenetic energy for 240bhp at 7,000rpm. What have they been feeding it? Vodka Red Bull seems the only logical answer. So much noise, so much agitation, such instantaneous response, and that long gearlever? You’ll be amazed how short and precise the shift is. Before you even contemplate the chassis you’ll realise you’re piloting a driving addiction. Yes, it’s hard work and tiring, but so it should be. This is a car with small dog syndrome. Eagerness overload and you’ve got to pedal hard to keep up. So you barrel over the ground, grabbing gears, heel-and-toeing, muscling the steering, listening to four angry, angry cylinders and very soon you realise that almost nothing you’ve ever driven moves along tarmac better than this.

It’s small so you always have line and trajectory options, it’s light and that means it has the agility of a wasp, and it’s mechanical so communicates in a way you understand. Small, light and mechanical: no wonder filter-free dexterity oozes out of it. Gordon Murray has an Alfaholics, which tells you everything you need to know. 830kg for 290bhp/tonne! If you tick other boxes (titanium suspension and full carbon body panels are the big wins) you can get it down to 780kg. Personally speaking, I’d actually back it off a bit. The front end is stiff, I’d like it to be a fraction more pliant on road and maybe with a less aggressive tyre than this Yokohama, but really, I can’t get over this little thing. It’s been beautifully engineered and beautifully set-up.

It’s an addiction and, for me, even better to drive than the Singer. Over the course of the day I swap cars and drive each in turn, chasing or being chased across these roads. It’s a delight, the experience enriched by looking out the windscreen or in the rear view mirror and having the other there, looking glorious and moving well. My earlier concern dwindles now the car is in its happy place. It loves to be muscled around, and once I’ve got to grips with it, discovered the nuances, this little terrier just comes alive in my hands.

Both are modern quick (with 290bhp per tonne, the Alfa has the same power to weight ratio as a new BMW M3, the Singer 360bhp/tonne), but still have the integrity and sensation of their historic selves. Well, the Singer does. Only the racing Alfas of the late Sixties had this sort of fury contained within them. In truth the Alfaholics has sacrificed some of its previous self on the altar of driver appeal, the string from 1967 to today has a few tangles in it. To me, it’s all the better for that. Light and largely recycled, this feels like a very relevant car in 2020, a total antidote to the binary electric future that now seems to be set out for us.

The Singer is more relaxed, arguably has more depth to it because there’s more than one way to drive. It’s fine following other traffic in the GTA-R, the signals are diligently fed back, but you’ve put it on a leash. The Singer is more placid in those situations, gives you a better fallback position – you can just sit there and admire the stunning cabin, relish the feel of the controls at your hands and feet, soak up the ambience. On the clear, empty roads you see in these pictures I’d drive the Singer hard one minute, then find myself just rowing through the lovely close ratio gearbox, or driving over particular sections just to geek out at how professionally the Ohlins dampers deal with tricky tarmac.

All the characteristics we know about old 911s – the way they swing into corners, the throttle adjustability and traction, the steering fidget and wriggle – it’s all here. It shouldn’t work to give a car with this set-up so much power and speed, but that’s the Singer’s secret – it does work. It’s a beguiling car.

And, like the Alfaholics, not simply a straight restomod. Porsche 911 reimagined by Singer, that’s the official wording. And you know what? That word is utterly perfect – Reimagined. There’s more going on with it, a West Coast vibe, a hint of ostentation and interpretation, a well judged cosmetic enhancement that the Singer more than carries off because it’s been applied just as skilfully to the dynamics as to the aesthetics of this sublime car.

There’s no winner here. Given an empty B-road I’d take the Alfaholics, given most other drives it would be the Singer. The Alfaholics surprised me more because despite knowing what’s been said and written about it before, I didn’t think it could be that good. It emphatically is. The Singer had been built up in my mind so much it could do no more than fulfil my expectations.

But what they do, both as a pair, and as part of the larger restomod scene, is show the sports car manufacturers of today, caught up as they are in their endless power wars, that there’s another way. Yes, these cars are very expensive, supercar, hypercar money, they exist at a financial pinnacle few of us can reach, and I doubt we’ll get much trickle down from them back into modern machinery of any budget. The vast majority of sports cars, unfortunately, are bought by those wanting bigger, faster numbers. The rest of us, those who care about experience, can just dream. And when we wake up, having dreamt about piloting deft slivers of driving perfection down endless B-roads, at least we’ll know that dreams can come true.

Trending this week

- 2026 TopGear.com Awards

"Engineering at the cutting edge": why the Ferrari F80 is our hypercar of the year