Here’s why swapping out your bike's suspension isn’t a bad idea

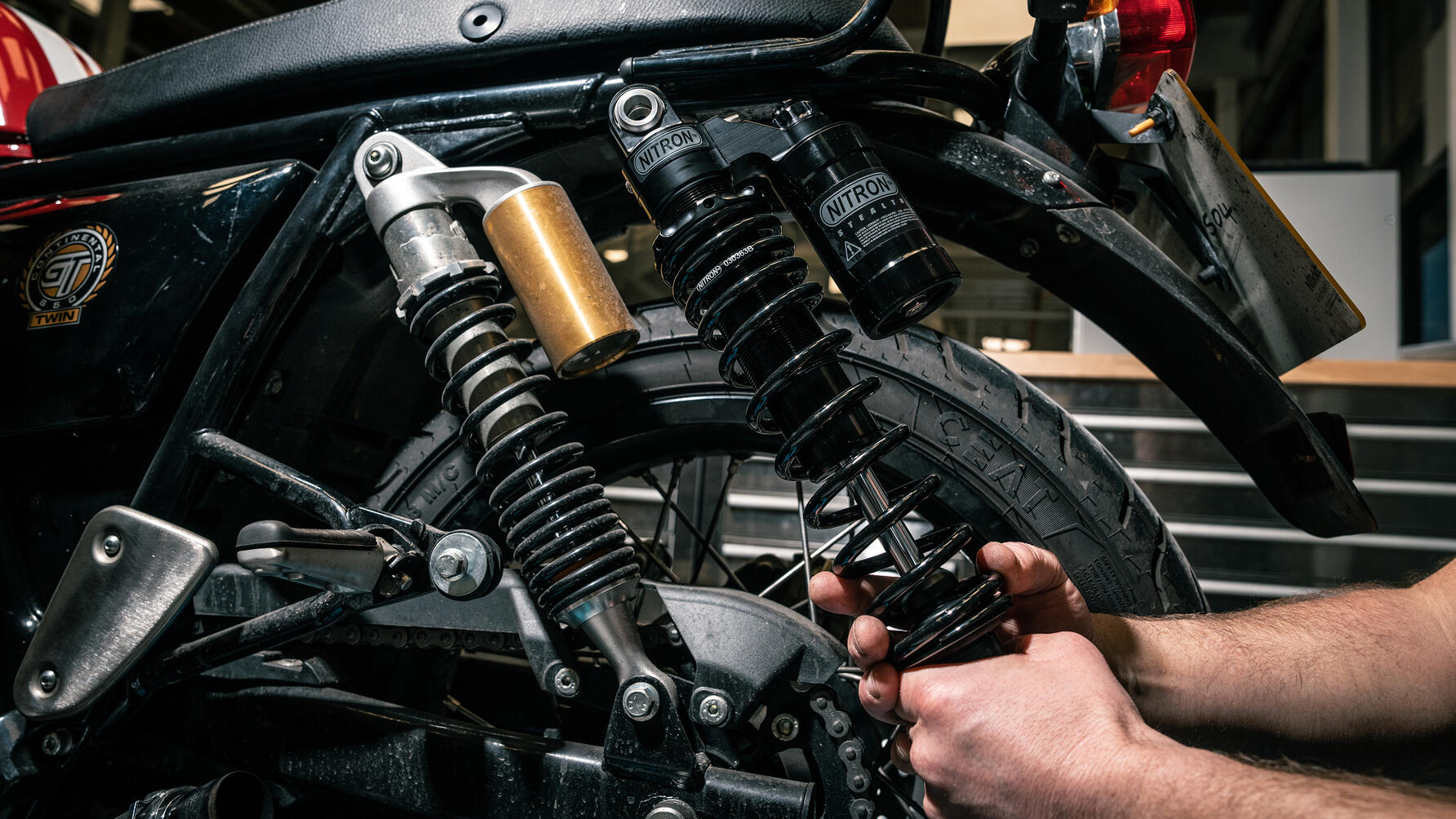

Woo! It's finally time to roll up our sleeves and get to the oily, as this month I took our Continental GT project bike to British suspension gurus Nitron (they of race car and fast Lotus fame) for its first major upgrade: new shocks.

Now, it probably won’t surprise you that swapping out the dampers on a budget bike is quite a simple yet very effective way to sharpen up its dynamics. And don’t let the GT650’s standard shocks fool you. They may look ritzy painted gold, but with very basic preload, fake reservoirs and limited travel, Royal Enfield’s stockers aren’t much cop. But what would you expect on a bike that’s less than £6k?

As soon as you sit on the bike, grab the front brake and rock it back and forth, the see-saw you’ve created shows exactly how soft the standard set up is. Admittedly, because the bike isn’t very powerful (47bhp), it’s not such a big issue if you’re keen on bimbling around. But as soon as you start to push the bike in any way, the shocks become increasingly overwhelmed and the dynamics start to fray as it has a tendency to bottom out.

“The main purpose of a shock/damper is to take the energy of a vehicle, calm it down and turn said energy into heat both consistently and effectively,” said Guy Evans, the adventurous (he once drove a Land Rover to Australia, got to India and had to turn back) son of a military test pilot who doubles up as Nitron’s founder.

But a damper needs to also be able to take a hit and deal with our broken corduroy British B-roads. A good damper will iron out the oscillation and return to normal as quickly as possible. A great damper does this with such aplomb it maximises the contact patch of a tyre to give consistency of grip which gives you more confidence as a rider/driver. This is Nitron’s raison d'etre and ultimately what they’re striving for.

It's not easy though. Unlike other parts – say a wheel – suspension is a subjective matter. And a shock absorber is an exceedingly complex part. Unlike said wheel, your purchasing decision isn’t based simply on what it does, how much it weighs or if it looks any good. When buying suspension you obviously consider those things, but then you need to fold the complexity of how it works and, most importantly, how it feels into the mix. To engineer feeling into something isn’t easy. That’s why Nitron has spent the last 25 years scratching their beards and smashing their heads into the table trying to perfect it.

The development process is astonishing, one where you have to juggle seemingly infinite variables. Things like; what materials to use, the molecular make up of them, their surface finish and coatings that work with them. Then there’s friction quality, valving, reaction speed, plus compression and rebound frequency. Are the bushes high or low? What’s the wear rate? And is the overlap of the damper design strong enough? It’s a monstrous task. And you’ll never look at a simple tube and spring in the same way ever again.

Thankfully Scott Maskell (Nitron’s bike suspension guru) had a kit for us that bolts straight onto the Conti GT650 and should revolutionise riding the bike. For Royal Enfield’s 650cc products a choice of two rear twin shocks are available; the NTR R1 (£590) which offers a one-way combined compression and rebound adjustment, and the NTR R3 (£1,099), which offers independent high and low speed compression and rebound adjustment. No matter what you buy, everything is hand built and offered in either the iconic Nitron turquoise blue or blacked out ‘Stealth’.

As we want to do big miles and engineer some sort of new versatility into the bike, we went for the more expensive NTR R3 in black as it offers a huge amount of adjustment (24 clicks of rebound, 16 clicks of high-speed compression and 16 clicks of low) which we can play with. Plus, they have proper, purposeful external reservoirs that look rad.

Up front, we’ve swapped out the front fork cartridges. RE’s standard front fork is a simple steel rod with a two-stage spring and damper rod. All filled with basic oil. Even to a billy like me, seeing the innards of Nitron’s set up splayed out over a workbench made you appreciate how technical and well-engineered they are.

Made from a mixture of aerospace grade aluminium and stainless steel, they should reduce mass and inertia whilst improving cooling. They’re also CNC billet machined, so beautiful. But also titanium anodised for protection against corrosion, while Teflon-lined bearings and bushes stop metal-on-metal friction – meaning they should last. Oh, and compared to standard, there’s a third piston shim stack for very low speed rebound control, plus Nitron’s triple valves should be far more reactive to road conditions and you can alter the rebound and compression like a Porsche GT3 RS.

Now we’ve just got to get clicky and dial them in. Which Nitron encourage users to do and get away from the factory settings. So here’s a top tip: go to the extremes of soft and hard first to see the vast difference you’re playing with, then go back and set rebound first, then compression. Go for the fastest rebound before it gets jittery and then finesse from there. It’s all stuff we’ll do when the bike is nearer completion, but boy it feels good to be playing with some proper upgrades.

Featured