BMW 327 and 328 review: new Z4's grandparents driven

The gearlever in a 1939 BMW 327 starts somewhere near your ankles. From there a spindly protrusion crested by a Bakelite lozenge emerges from the footwell to a hovering central mid-air point. There is plenty of space around it. This is important. Because not only is the lever itself long enough to use as a walking cane, but first and second are a lengthy stride apart.

I have a rummage for them. First rule: don’t place fist over gearknob. Two reasons: firstly, that’s a thuggish way to manipulate the gears of a 1939 BMW 327 Roadster, and secondly, you’ll smack your knuckles on the dash while finding first. It’s up there somewhere. So instead place thumb on top and cup the underside between index and middle finger. Ahh, that’s better. Now, arm out straight, prepare your shoulder for the downwards sweep into second. You don’t need too much muscle, just let your arm go heavy and drop down between the seats. You’ll find second when the lever is parallel to the transmission tunnel and your knuckles touch carpet.

At least things are familiar. The pedals are in the correct order, the gearbox is an H-pattern manual, there’s no fooling about with retarding the ignition or juggling extra levers and the engine – get this – is a straight six, a layout BMW is still championing. And this car is almost 80 years old.

Why am I driving it? Let’s call this a reminder. There’s a new Z4 coming out (we drive it soon) and we can pretty much guess what it’s going to be like. The last one. Because big companies don’t take risks. In fact these days they often need to team up to make things happen. So the new Z4 shares platform and mechanicals with Toyota’s new Supra.

This homogenisation is a byproduct of the modern motor industry, and sometimes it’s good to remind yourself that things were once done differently. By driving a 1939 BMW 327 and realising that there are drawbacks. Chief amongst which is no rearwards visibility whatsoever: no mirrors on the flanks and the central mirror’s view comprehensively blocked by the stacked hood. And performance that means when I pull out on to a country lane behind a Land Rover and trailer and inwardly groan, I then have trouble catching up.

That’s lovely actually, to feel you’re exercising the car, but still travelling at a modest pace. The 327 isn’t big, but it is elegant with its sweeping tail, rear wheel spats and comparatively calm road manners. I’m now on an even tinier single track country lane, praying nothing comes the other way. I’m up to third, down to second, getting the hang of it, when a tight left up a steep hill comes into view. With dog walkers coming towards me. In modern stuff this is simple: hit brakes, wait for them to pass, continue. In old stuff it’s a juggle.

I was in second. I brake and attempt to find first at the same time. Achieve both. Now, do I go for the handbrake (which means ducking under the dash, as it’s somewhere down the far end of the footwell) or dare I ride the clutch and try to continue? “Keep it going, keep it going!” exhort the walkers, urging me on. The 327 has that effect. So, I attempt to judge throttle and clutch positions, making sure the gearlever is still roughly in the right place. All my limbs are busy. I still stall.

Now I have to restart and pull away up a steep hill. Stress. Especially with tall dogs sniffing over the doors. But actually I’m not stressed, the car is basically a bonding instrument between driver and walkers. They’re entranced by it, ask where’s safe to push from and help get me going again. It’s a lovely countryside evening experience. Once rolling I give a quick poop-poop on the horn, blip the throttle as I arm-drop into second, and rasp gaily away.

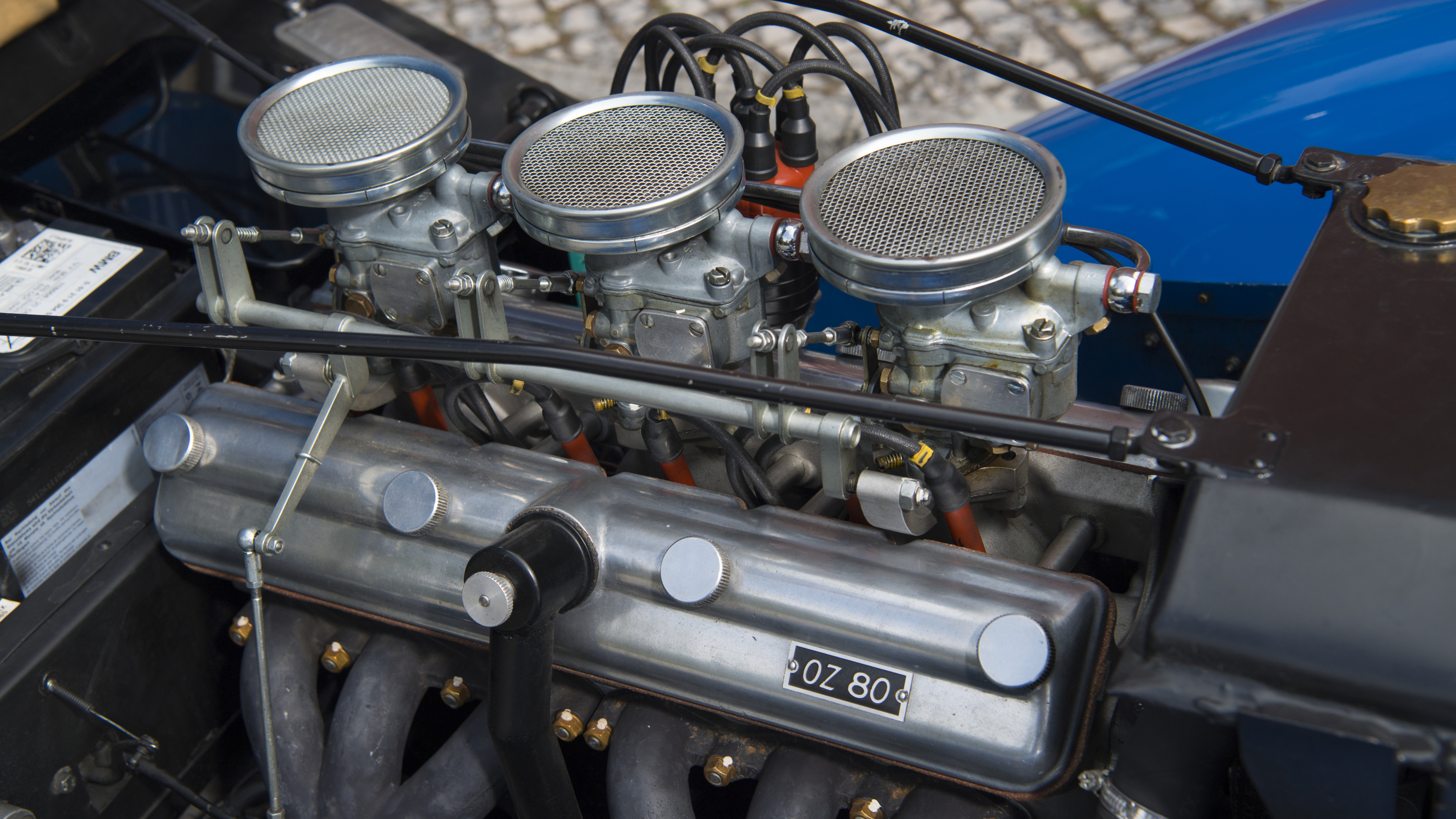

And boy does the 327 rasp well. Up into what I can only assume is the mid-range (there’s no rev counter) it sounds utterly magnificent. Genuinely sporty, a proper six cylinder bark that’s at odds with the genteel looks. And yet that motor is honey smooth, vibrations minimal. 80bhp from the uprated M328 engine (lesser 327s made do with the 55bhp M78 motor) for a 78mph top speed. 569 were built before war broke out.

Great though the 327 is, it’s always lived in the shadow of the car it was built alongside, the numerically superior 328 (the blue car, above). Same 80bhp M328 engine, but this was a sports car, not a tourer. It was lighter, 830kg instead of 1,100kg, so faster to accelerate and benefiting from a 93mph top speed.

Top Gear

Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter. Look out for your regular round-up of news, reviews and offers in your inbox.

Get all the latest news, reviews and exclusives, direct to your inbox.

I sit lower in this, eyes almost level with the bonnet. Same switchgear, slightly smaller arc to the gearlever, but immediately a firmer, more informative ride. The back axle is solid, supported by half-elliptical leaf springs and over bumps as much flex seems to come from the body as the suspension. It’s not just the scuttle that shakes, but the steering column, seats, pedals and so on. Yep, you feel everything.

But with the little half doors, low tail and compact dimensions (less than four metres long, only one-and-a-half wide), it’s an immersive experience. Got hair? You’ll have a rear parting within a mile. It does feel rickety, but it’s an alert little machine. Barely any slack in the steering, either. You turn, those skinny disc-like front wheels respond. Rack and pinion steering, see? Yep, back in 1936.

This car, same as the 327, is badged a Frazer-Nash BMW. Frazer-Nash was the UK importer of BMWs before the war. This very car raced at Brooklands. It’s valued at £750,000. About £1,000 per kg, then.

Featured

Trending this week

- Car Review

Toyota Urban Cruiser

- Top Gear's Top 9

Nine cars with infamous, weird and quite wonderful windows